I love the Macintosh. A lot.

Even though I wasn’t really exposed to these computers until 2015 when my dad bought a MacBook Air, my appreciation for them runs deep. It’s why in middle school I rocked a 5th generation iPod nano - the only Apple product I could really afford at the time beg for as a birthday gift.

My path to computing started elsewhere, though. My first computer was a netbook running Windows XP - half a gig of RAM, 64GB storage, and an Intel Atom processor. That netbook became my introduction to Linux, Bash scripting, and the command line - not by choice, but by necessity.

To me, programming was never a product-focused endeavor. It was always an art-based journey, where you’re given a blank canvas to create anything of your liking. It’s one of the very few art forms that transcends the mere observer into interacting with the art form itself. The audience doesn’t just look at what you’ve made - they use it, live with it, make it part of their daily routine.

There are two sides to the technology spectrum, and understanding both helps explain what makes the Macintosh special.

On one hand, you have the pragmatists. Enterprise customers, Linux sysadmins, people who insist upon maintaining backwards compatibility so hard that a leap year bug in Lotus 1-2-3 from 1980 remains a bug in the latest Windows 11 version of Microsoft Excel. I’m not trying to denounce them - these computers and programmers do important work. Everything in this field is built upon what came before, layer after layer, creating the systems we have today. But this approach comes at a cost: your operating system starts to feel bloated, retaining outdated elements from earlier versions like archaeological strata. Peek at the Registry Editor in Windows and you’ll still find remnants from Windows 95, some even from Windows 3.1.

I knew this bloat intimately. My second computer, an HP laptop, crawled under Windows 10’s bad resource management and a mechanical hard drive. Ubuntu became my daily driver again, and that early command line exposure taught me more than any CS class could have. These systems exist because they make the world go round. Any change can make heavy and expensive equipment stop functioning, or cause millions of databases and scripts to crash.

On the other side of the spectrum, you have Apple. A company that offered its products in such a fast-paced yearly cycle that it was almost never taken seriously in the enterprise world during the early days. Despite their shortcomings (and there were many, including the 1984 Macintosh being underpowered and overpriced), they got one thing right: how to make a great UI. When it comes to good design, this is the big leagues.

My fascination with Apple started around 2011-ish, with the advent of the iPhone 4. I didn’t know the cost, or even understand the high status attached to it. What I knew was that when I saw a family member use it, the OS felt cohesive and smooth. It felt sleek, natural, and almost like a joy to use. I’ve been exposed to iOS products since, and they’ve all felt like pure joy to use. For a very long time, I customized my Android devices to look like an iPhone (barring a minor time period when I used Windows Phones).

In a way, I was a reverse Macintosh user. For many years, I didn’t even know the Macintosh existed. I used my iPod nano with the Windows partition + iTunes on my laptop, and the family iPad to get stuff done, and I knew of the iPhone from watching other family members use it. That changed in 2015.

When my dad brought home that MacBook Air, something clicked. This wasn’t just another computer. After years of fighting with underpowered hardware and bloated operating systems, here was a machine where things just worked. Not because I’d optimized it or stripped it down or found the right combination of command line tools, but because someone had actually thought about how the pieces fit together. It was a tool, in the truest sense of the word.

Mac-assed Software

I got my first personal Mac in 2020 - a 2016 MacBook Pro. The butterfly keyboard was already notorious by then, but I didn’t care. The hardware blew me away. The trackpad wasn’t just responsive, it was precise. The haptic feedback felt intentional. And those speakers - I still don’t understand how they got that much sound out of a laptop that thin.

But it wasn’t just the hardware that felt different. It was how everything fit together. The hardware and software weren’t just coexisting, they were designed for each other.

Except when they weren’t.

VS Code on macOS felt wrong. Not broken, not buggy, just… off. Like wearing shoes that are technically the right size but don’t quite fit. The keybindings fought with system shortcuts. The UI elements didn’t quite match anything else. Opening files felt sluggish compared to native apps. It was a web app pretending to be desktop software, and the seams showed. Similarly with Google Chrome: the only app I have seen that makes you HOLD ⌘Q instead of just pressing it once.

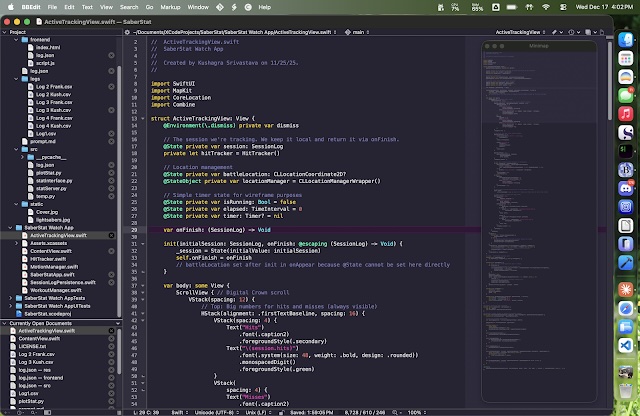

I started looking for alternatives. Not because I’m a purist or because I wanted to be difficult, but because I was spending 14 hours a day in my editor at times and the friction was adding up. That’s when I discovered what John Gruber calls “Mac-assed Mac apps” - software that doesn’t just run on macOS, but feels like it was made for macOS. Software that uses native UI elements, respects system conventions, and integrates with the platform instead of fighting it. BBEdit was the first one I found. Then Scrivener for longer writing. Then a whole ecosystem of tools made by people who actually cared about the craft of software, not just shipping features.

Looking back, every single thing I’ve done that’s been worth a damn has been done on a Mac. Because the tools on a Mac felt like they were created by people who gave a damn.

My undergraduate thesis. My research projects with iCons at UMass. Work with the Museum of Science that incorporated GIS, real-time data collection, and improving public transit. Creating a simulations platform to improve HVAC usage at UMass. The AI-supported electricity restoration tool I built for the U.S. Census Bureau. My contributions to STORMM, where I reduced compilation requirements from 70GB of RAM to laptop-grade specs and cut build times from 40 minutes to 9. Starting an (albeit short lived) undergraduate research lab. Among countless others that I haven’t mentioned, and the ones that are currently in progress.

All of it on a Mac. All of it using native tools.

It wasn’t a conscious decision at first. I wasn’t trying to be a Mac evangelist or prove a point. But there was something about these tools that just got out of my way and let me work. BBEdit didn’t need 24 extensions to be useful. Scrivener understood that writing long documents is different from editing code. These were craft instruments designed by people who understood the work.

In the meantime, I upgraded to an Apple Silicon MacBook Air in 2024 and incorporated a Mac mini in 2025. But these are side details.

In April 2024, I wrote an appreciation email to Bare Bones Software while sitting at a cafe. I didn’t really plan to, it just happened. I’d been using BBEdit for years at that point, and I wanted them to know what their software meant to me. I compared it to flying an F-18 versus driving a Toyota Prius - not because the Prius is bad, but because the F-18 is built for a specific purpose and does that purpose incredibly well.

Rich Siegel, the founder and CEO, wrote back personally. Not a form letter, not a marketing response, but a real email thanking me for understanding “the BBEdit ethos.” Surprisingly, as a gesture of goodwill, he also sent me a merch bundle that I still wear to this day. To this day, I am extremely thankful, and speechless, for this.

I was deep in my thesis at the time, so I didn’t respond for months. When I finally did thank them, it was buried in a support email about something else entirely. It was acknowledged by Patrick Woolsey: another longtime BBEdit Product Designer and Programmer who thanked me personally. Believe me, I have never been touched so deeply with a group of people who care. Care about the product, and care about the users.

That’s when I realized I’d stumbled into a community of people who cared about software the same way I did.

*(Disclaimer: Please do not inundate Bare Bones with emails in hopes for merch. This is my appreciation to them. I would very much appreciate it. Also, if you have a Mac, try out the Free version of BBEdit). ***

The Macintosh PowerBook G3

My fascination with computing history had been growing alongside my appreciation for well-crafted software since middle school. I’d been learning about early Apple, about the Macintosh, about the era when personal computers were still figuring out what they wanted to be. Alongside, I also listened to and resonated a lot with the free/libre software sides of the argument, the open source argument, and different takes on copyright, how to write software, why “write once run anywhere” is a good idea, why “write once run anywhere” is an awful idea, and so on. At the end of the day, I believe that I am a pragmatist when it comes to this stuff: I would want libre software to be the norm and often license my own code under the GPL v2/v3, but I understand how Open Source MIT licenses are more appealing, and so on.

Off track.

I found a PowerBook G3 for $50 on Facebook Marketplace in early 2025.

This wasn’t just collecting vintage hardware to put on a shelf. I wanted to use it. To understand what development was like during that era. To see if the philosophy that made BBEdit great in 2024 was the same philosophy that made it great in 2001.

But there was a problem. I needed BBEdit for it. And Project Builder, Apple’s predecessor to Xcode. So I reached out to Bare Bones again. Years after that first appreciation email, years after they’d sent me merch, I sent another email asking if they had any way to get old versions of BBEdit that would run on Mac OS X Jaguar and System 9.

Patrick Woolsey responded. They couldn’t provide old versions of BBEdit directly due to licensing issues, but he pointed me to BBEdit Lite 6.1.2 on a vintage software archive. Then, when I needed more, the Vintage Mac community went further - with links hosting these old software versions on Macintosh Garden.

I got it running. BBEdit and Project Builder, on a PowerBook G3, with a complete early 2000s development environment (I also needed StuffIt Expander to uncompressed files and Roxio toast to mount disk images). I wrangled with an example simple multi-window application in Objective-C and C++. The build succeeded. The app ran.

And here’s the thing that got me: this 23-year-old version of BBEdit still has about 80% of all the features in the modern version. All my muscle memory transferred. All my keybindings worked. The fundamental design was so solid in 2001 that it didn’t need to be reinvented.

Just for context, I was born in 2001.

That, is the beauty of Mac-assed Mac software.

What I’m Building

I’m working on porting some modern C++ tools to this PowerBook G3. I’m not ready to reveal exactly what yet, but the project has taught me something important about software design.

When you strip away the bloat - when you can’t rely on gigabytes of RAM and multi-core processors to paper over inefficiencies - you have to think carefully about what actually matters. The PowerBook G3 forces that discipline. It’s not fast enough to forgive bad code or lazy design decisions.

But it’s also not about the hardware limitations. It’s about understanding what made software from that era feel different. ProjectBuilder and BBEdit weren’t trying to be everything to everyone. They had a specific purpose, and they did that purpose exceptionally well. They were tools designed by craftspeople for other craftspeople.

Modern development tools have incredible features. IntelliSense, live debugging, integrated terminals, AI code completion. But somewhere along the way, we lost something. We started building tools that require constant internet connections, that need hundreds of extensions before they’re useful, that feel the same on every platform because they’re not really native to any platform.

BBEdit from 2001 doesn’t have AI code completion (though it has AI worksheets that even work with local LLMs, and handle all chat data processing in a text file). It doesn’t have a million extensions. It is not cross platform (shocker). But it opens instantly, handles massive files without breaking a sweat, and respects the user’s intelligence enough to provide powerful features without hiding them behind layers of abstraction. And I genuinely mean massive files: 20+GB of text without breaking a sweat.

That’s what I’m exploring with this project. Not nostalgia for old hardware, but an investigation into what we lost when we decided that “cross-platform” was more important than “well-designed for one platform.”

The PowerBook G3 sitting on my desk, running software from 2001, can still do meaningful work in 2024. It’s a testament to the software design philosophy that created tools meant to last.